8:00am—9am

Registration (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Foyer)

Breakfast and Coffee Service (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 110)

- Assorted breakfast tacos from Taco Cabana

- Coffee service from Mocha & Java

9:00am—10:20am

- Diplomatic Response to Native and Foreign Powers Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 201) Faculty Commentator: Margaret Vaverek, Librarian, Texas State University, and Jason Rivas, Graduate Student, Texas State University

Student Moderator: John Rogers, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Issac Xaiver Auld, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Comparative Analysis of the United States, France, and Spain’s Use of Neutrality in 1776 and 1793’”

- Christopher Bragdon, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Effects of Cherokee Nationalism and American Public Opinion on Early S. Diplomacy”

- Kendall Jo Allen, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Education as a Diplomatic Tool in Negotiations with Native People”

9:00am—10:20am

Transformations in Architecture Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 106)

Faculty Commentator: Dr. Peter Dedek, Associate Professor, Texas State University Student Moderator: Kyla Campbell, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- Kyle Walker, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Spanish Colonial Revival Architecture’s Role in the Preservation Movement in San Antonio”

- Mary Kahle, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Architecture of Moral Treatment for the Mentally Ill in Nineteenth Century S.”

- Nikolas Koetting, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “‘A Comparative Analysis of the Architecture of Charleston and New Orleans

9:00am—10:20am

Decolonization and the British Empire Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 105)

Faculty Commentators: Dr. Nancy Berlage, Director of Public History, Texas State University Student Moderator: Francisco Rodriguez Arroyo, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- Rayanna Hoeft, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “A Collection’s Purpose: Connecting Material Culture to Museum Visitor Experience”

- Messia Gondorchin, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Misunderstood Monuments of a Forgotten War: Commemoration of the Second Boer War throughout England”

- Desmond Workhoven, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Barton Brothers: Privateers and Founders of the Scottish Navy”

10:30am—11:50am

Thomas Jefferson and National Leaders Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 201) Faculty Commentator: Dr. Shannon Duffy, Senior Lecturer, Texas State University Student Moderator: John Rogers, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Christian M. Prado, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Nature and Nurture: How Human Tendency and Exterior Influence Affected Early Diplomatic Policy”

- Samantha S. Cayse, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “North African Pirates and American International Affairs: Evolution of Jefferson’s Diplomacy with the Barbary States”

- Asher C. Rogers, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Jefferson’s America in the Age of European Colonialism: Western Territories & the Louisiana Purchase”

10:30am—11:50am

Gender and Women’s Identity Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 106)

Faculty Commentator: Dr. Jessica Pliley, Associate Professor, Texas State University Student Moderator: Messia Gondorchin, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Jennifer Blackwell, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Two for the Price of One: The First Ladies and American Diplomacy Beyond the Confines of the Women’s Sphere”

- Lauren Kahre-Campbell, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Gendered Patterns of Inheritance in Early Modern England”

10:30am—11:50am

Foreign Policy and War Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 105)

Faculty Commentator: Dr. Ellen Tillman, Associate Professor, Texas State University Student Moderator: Desmond Workhoven, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Evan Moore, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Continental Army’s Role in Violence at the Battle of King Mountain”

- Andrew Freeman, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “From Tampico to Niagara Falls: How a Perceived Insult Led to Invasion, Occupation, and Mediation”

- Robert J. Anzenberger, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Herbert Hoover: Finland’s Guardian Angel”

12:00pm—12:30pm

Lunch catered by Mamacita’s (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 110)

12:45pm—1:45pm

Keynote Presentation (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 101)

- Dr. Thomas Cauvin, Assistant Professor at Colorado State University and President of the International Federation for Public History

2:00pm—3:20pm

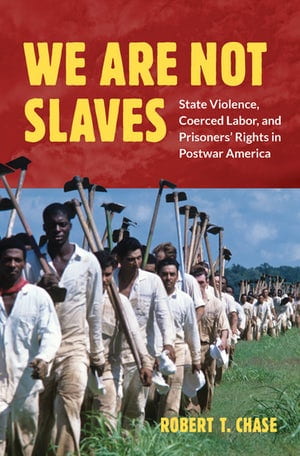

The Continuous Role of Slavery in Revolutions and Diplomacy Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 106)

Faculty Commentator: Dr. Dwonna Goldstone, Director of African American Studies Program, Texas State University

Student Moderator: Messia Gondorchin, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Ana Sofia Hernandez, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “‘The Impact of the Haitian Revolution on Early American Diplomacy Towards Slavery”

- Reagan Deona Sekander, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Annexation of Texas and the Issues that Slowed the Process”

2:00pm—3:20pm

Perspectives in Modern History Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 105)

Faculty Commentators: Mr. Dan K. Utley, Lecturer, Texas State University and Dr. Jeff Helgeson, Associate Professor, Texas State University

Student Moderator: Desmond Workhoven, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Suzanne Schatz, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Fire Burns On: Texas A&M Bonfire, Women, and Tradition”

- Ethen Peña, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Yellow Stained Tears”: The Effects of Historical Trauma on the American Indian Movement”

2:00pm—3:20pm

The Chains of Early American Diplomacy Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 201) Faculty Commentator: Dr. Sara Damiano, Assistant Professor, Texas State University Student Moderator: John Rogers, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Tobi Omo-Osagie, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Racial Barriers to American Diplomacy”

- William Joseph Keenan, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “By Way of the St. Lawrence: The Bond of Slavery in Canada and The United States”

- Alex J. Humphries, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Faith of the Confederacy Rests on Cotton”

3:30pm—4:50pm

The Beginnings and Impact of the Monroe Doctrine (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 201)

Faculty Commentators: Dr. Thomas Alter, Assistant Professor, Texas State University, and Rayanna Hoeft, Graduate Student, Texas State University

Student Moderator: John Rogers, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Hannah Thompson, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: How Early American Presidents Paved the Way for the Monroe Doctrine”

- Sarie Aguirre, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Advancement of American Imperialism through The Monroe Doctrine”

- Illeane Marquez, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Monroe Doctrine: A Policy of Non-Interference for European Powers for Peace and Safety”

3:30pm—4:50pm

American Imperialism Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 106)

Faculty Commentator: Dr. Joshua Paddison, Lecturer, Texas State University Student Moderator: Messia Gondorchin, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Noa Vasquez, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “Conquest and Growth: The Two Ages of Filibustering”

- Carlos Fidalgo, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Texas Quagmire: How Failed Diplomacy Sparked the Mexican American War”

- Jacob Dowdell, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- “The Tempering of US Imperialism: The Cost of an Island Empire”

3:30pm—4:50pm

Military and Government Architecture Panel (Taylor-Murphy Hall, Room 105) Faculty Commentator: Dr. Peter Dedek, Associate Professor, Texas State University

Student Moderator: Desmond Workhoven, Undergraduate Student, Texas State University

- Kyla Campbell, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “From Barracks to Balfour: The Evolution of Base Housing on American Military Bases.””

- Evan Smith, Graduate Student, Texas State University

- “Washington D.C.: A Unique Creation of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries”