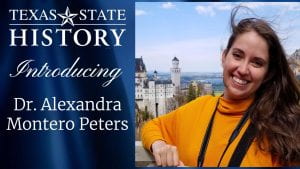

We’re delighted to welcome Dr. Alexandra Montero Peters as our new Assistant Professor of Medieval History! Dr. Montero Peters specializes in the history of the medieval Mediterranean, specifically the cultural and intellectual exchange between Muslims and Christians of Iberia, North Africa, and the Near East.

Ever since I was little, I have had a passion for the Middle Ages. I read every book I could buy or rent on King Arthur, and when it came time to go to college, I only applied to institutions that had a Medieval Studies major. However, before I began my degree, I had no concept of a Middle Ages beyond England, and as a heritage Spanish speaker—my maternal family is all from Ecuador—I didn’t realize that the cultural histories and language skills I had learned at home with family would change the trajectory of my academic interests to a different country and focus. In a fateful meeting with a professor of medieval history at my alma mater, UChicago, I discovered the world of medieval Iberia, sometimes called Spain of the three religions, and realized that I already had a key tool to dive headfirst into research: Spanish. It was a world that captivated me with its complex and fraught past of Islamic, Jewish, and Christian exchange, its rich artistic and literary traditions, and its overlapping history with Latin America. I could learn through the mirror of the past something about interfaith relations, a theme that felt urgent and timely, while at the same time growing in my own understanding of who I was and the past that had affected my own family across many generations.

Not long after diving into medieval Iberia as an undergraduate, I discovered a second passion on the dusty shelves of my library’s vast stacks. Filed next to my books in Spanish about Iberian history were rows and rows of Arabic tomes. This made perfect sense given the over 700 years of Islamic power in medieval Iberia. However, it sparked in me a curiosity to know more about how the books of the past—medieval manuscripts—reflected the close proximity of Christian and Islamic intellectual centers. What role, I asked, did interfaith relations play in how intellectuals of the period asked and answered some of the most pressing questions of their day, on everything from the power of freewill to the ways planets moved in the heavens above? How do manuscripts record for us their overlapping worlds, both literal and literary? Needless to say, this question led me to take years of Arabic, travel the world to study illuminated manuscripts in person, and it planted the seed for my current research on everything from medieval chess to race before modernity.

I am so excited to find myself at Texas State University, and I cannot wait for students to see the entwined histories of medieval and early modern Iberia with that of their own backyard. I will invite students to the fascinating world of medieval Iberia and many other cultures in my spring course on “Reframing Medieval Power.” As a big fan of staging historical simulations for students to tap into the past in meaningful, memorable ways, I’m doubly excited that this course features a multi-day, costumed, role-playing event where students embody real medieval people. They will scheme, negotiate, and perhaps even betray others as they vie for power, and I can’t wait to watch the drama unfold!

In my spare time and beyond the medieval, I am an avid nature photographer and a foodie, and I’m eager to learn from my new friends and students here where the best spots are for both hobbies. I also love to read new fiction, and before moving to the Texan heat, I also loved to run outside. We’ll see about that here!