Category: History at Texas State

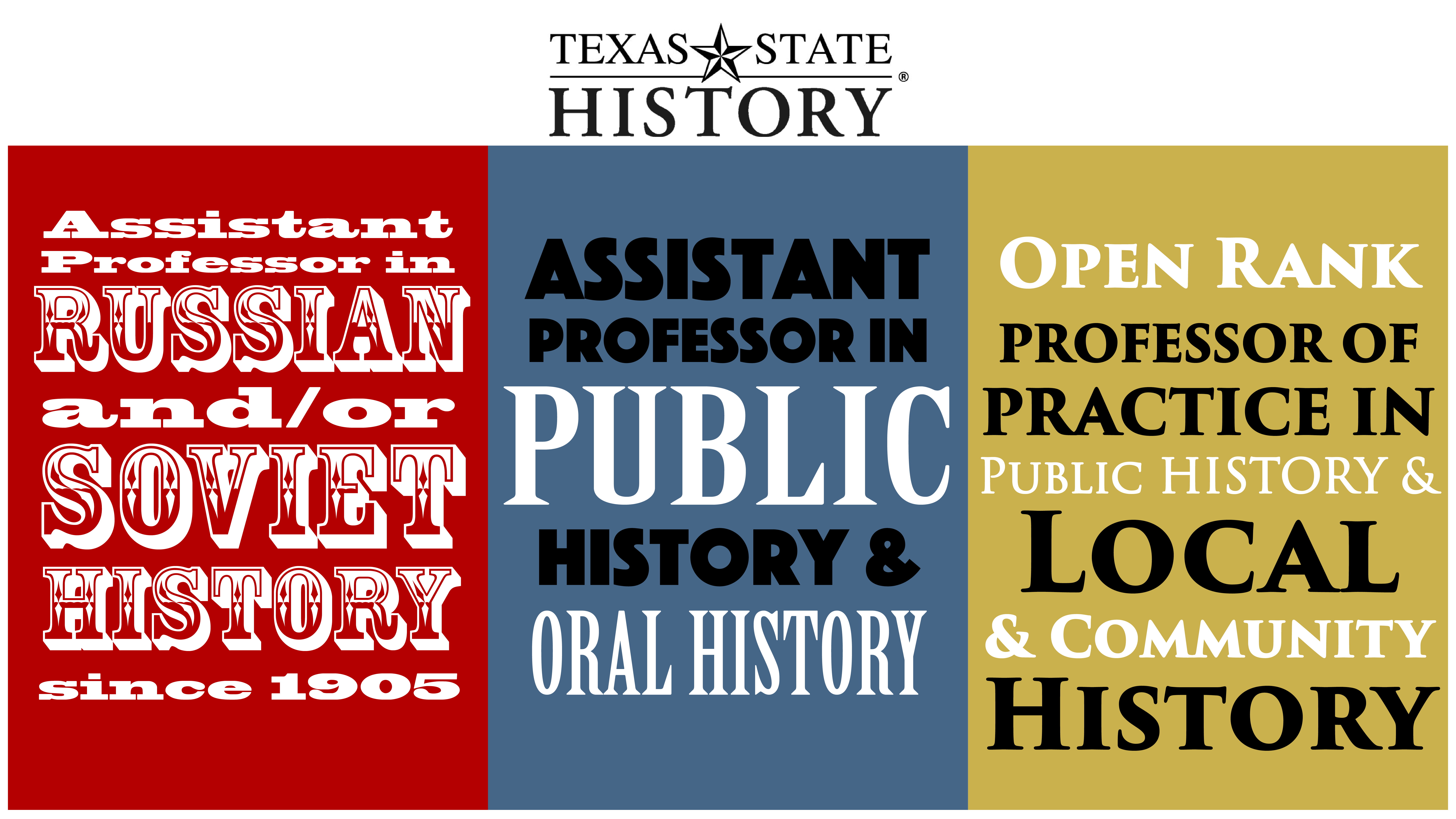

Now accepting applications

Texas State University’s Department of History is currently inviting applications for the following positions. Click below for details:

Assistant Professor in Russian and/or Soviet History since 1905

Assistant Professor in Public History and Oral History

Open Rank, Faculty of Practice in Public History and Local and Community History