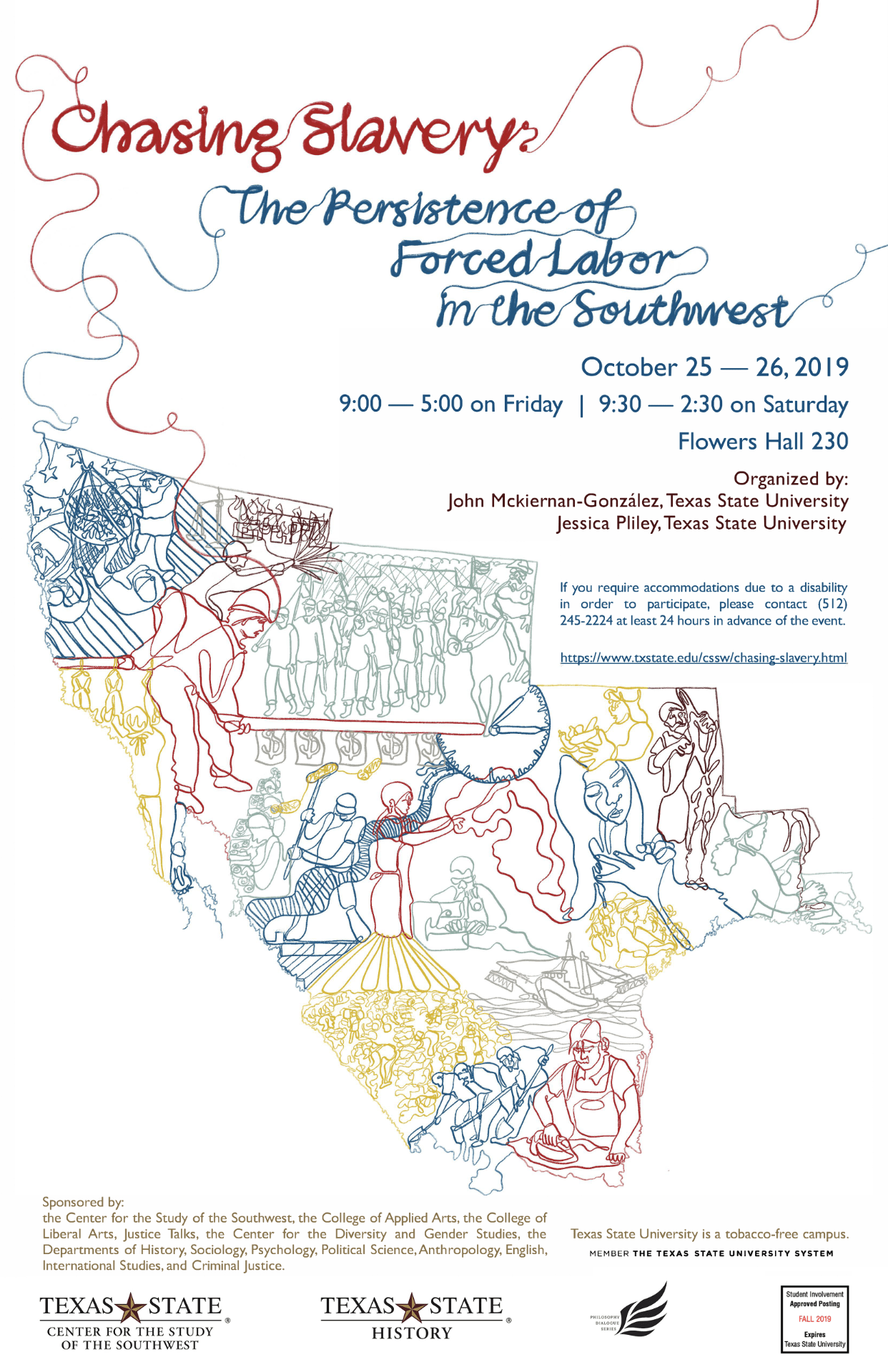

In preparation for the upcoming symposium, Chasing Slavery: The Persistence of Forced Labor in the Southwest, to be held at Texas State University from 24-26 October, in Flowers Hall 230, we will be running a series of posts focused on the conference participants and organizers. The conference will bring together dozens of scholars, with a keynote from Ambassador Luis C.deBaca (ret.). See the conference website for more details.

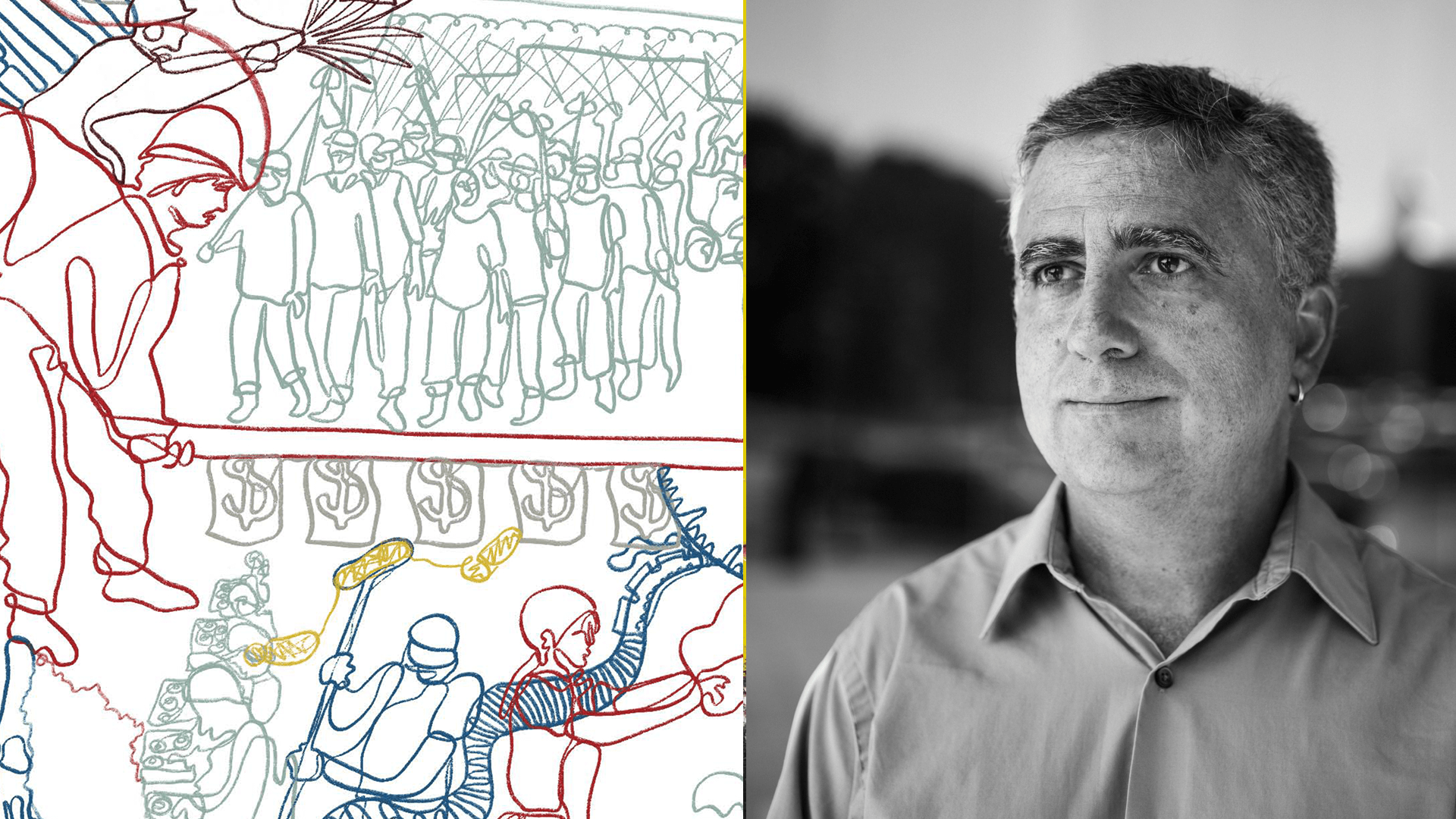

Today, conference co-organizer Dr. Mckiernan-González, Director of the Center for the Study of the Southwest and Associate Professor of History at Texas State University, helps introduce the conference for our readers. He can also be found on Twitter.

Give us your elevator pitch for the conference. What is it about?

Dr. John Mckiernan-González: In a broad way, this conference aims to help us understand why forced labor continued after the 13th amendment banned slavery in the United States, and how people used the constitution to change their situation. There is a thread in anti-immigrant politics in the United States that uses the rank exploitation of people in a given community to justify the expulsion or restriction of the presence of that community in the United States – rather than treating exploitation as a shared situation and part of a broader economic relationship. This problem has been explored in depth in the U.S. South for year, from the rise of peonage during Reconstruction to the establishment of Jim Crow, and that deserves continuing exploration. By bringing a variety of perspectives, we can understand the many ways the 13th amendment shaped labor relations in the past and present of our multi-ethnic, indigenous and immigrant Southwest. I want people to consider the criminal exploitation of workers, when conditions become visible and harsh enough to be considered a crime worth prosecuting.

In another sense, people should consider the way the challenge to forced labor, from peonage to labor trafficking, also involves a transnational response. Our keynote speaker, Ambassador Luis C. de Baca, worked with the founders of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers to prosecute their contractors and, in the aftermath, the C.I.W workers went on to create one of the more successful migrant labor movements in the country. As historians, we have the disciplinary space to explore what happens before and after a labor conflict becomes a criminal matter, and track what different people do after slavery and human trafficking has been charged. One answer can be: create a labor movement. Most of all, the conference should help us become more aware of the ways forced labor has shaped the Southwest.

What was the most surprising thing you encountered when researching the conference?

Dr. Mckiernan-González: Putting together the conference and the associated class on forced labor in the Southwest has been deeply educational. I now tend to see forced labor almost everywhere, either directly or lying in the wings. Most frustrating, of course, is when you realize key chapters in your work – in my case, my chapters on the (African American) Tlahualilo Colony and Camp Jenner in Eagle Pass would have been vastly improved.[1] I wish I had named the ways the medically detained refugees in Eagle Pass had to explain and challenge the contract they signed with William Ellis and the Tlahualilo corporation to demand help and resources from U.S. federal agencies. Along with a deeper appreciation of the presence of forced labor, organizing the conference has helped me think more broadly about the labor constraints facing men and women in stigmatized communities – from juvenile inmates in state asylums to deaf migrants in a transnational forced labor key chain ring.

What do you hope people will take away from our conference on trafficking, forced labor and labor exploitation?

Dr. Mckiernan-González: Hope. People have consistently challenged the constraints they have faced. Hopefully, people will leave the conference aware of the ways institutions maintain and have maintained forced labor in the Southwest and leave with an awareness that these struggles have a long and continuing history.

What challenge(s) raised by your research are you still trying to reconcile?

Dr. Mckiernan-González: Talking about the Chasing Slavery conference with soccer teammates and extended family has highlighted the way solidarity and coercion often coexist, from people sharing stories about adoption, smuggling debts to coyotes, to informal apprenticeships in semi-skilled trades like housecleaning and construction. As a historian who prefers text, I see a distant connection between what appears on paper and the everyday coercions working-class people face; the challenge lies in tracing these connections.

[1] John Mckiernan-Gonzalez, “’At the Nation’s Edge’: African American Migrants and Smallpox in the Late Nineteenth-Century Mexican American Borderlands,” Martin Summers, Laurie Green and John Mckiernan-Gonzalez, ed. Precarious Prescriptions: Contested Histories of Race and Health in North America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 67-90

Also check out: