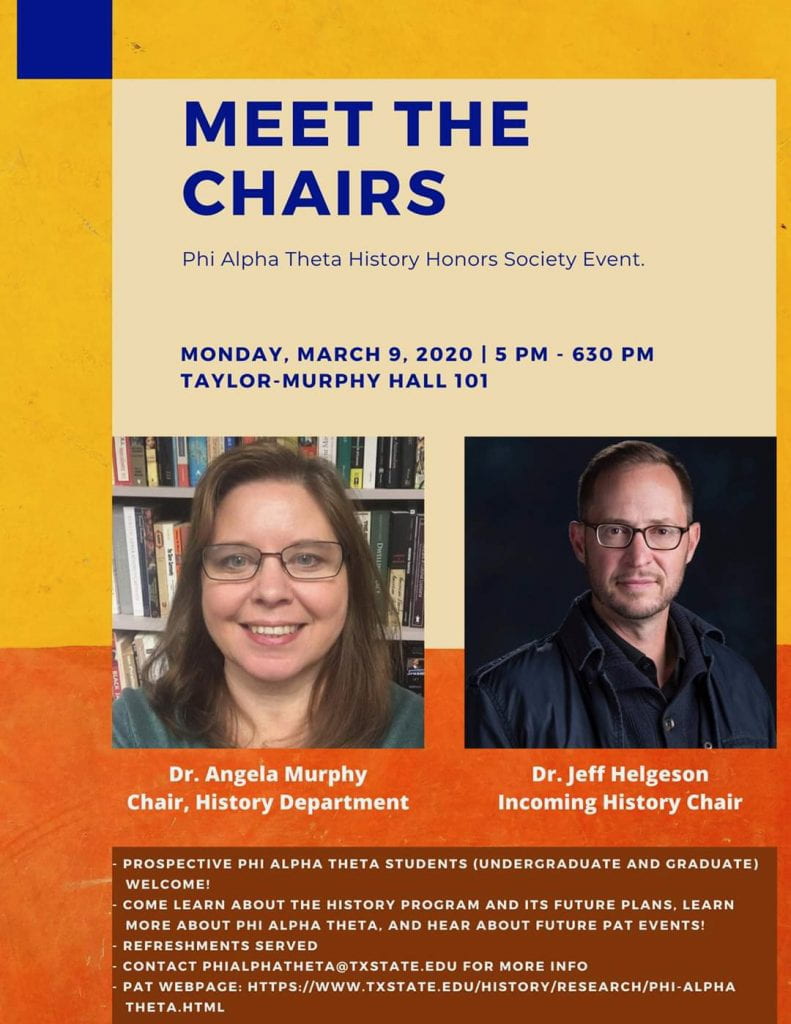

Dr. Angela Murphy, who has served as chair of the department since 2017, reflects on her time as chair and shares some of her upcoming research. Incoming chair, Dr. Jeffrey Helgeson, gives us a glimpse into his vision of the future of the department.

Join them both on 9 March 2020 from 5:30-6:30 PM in Taylor-Murphy Hall 101 for a discussion sponsored by Phi Alpha Theta History Honors Society.

A Note from Dr. Angela Murphy

A Note from Dr. Angela Murphy

It has been rewarding serving as chair of the History Department for the past few years. It has given me a chance to get to know students on a different level, beyond the classroom, and to help further the vision of my fellow faculty. Students should know that they are front and center in that vision. I am proud to say that although the department is made up of world-class researchers, student success has remained one of its highest priorities. This can be seen not only in the way in which faculty interact with students both in and out of the classroom, but also in the type of people we have hired over the past three years, in the efforts that have been put into modernizing the curriculum, and in the accomplishments of our students both while they are enrolled with us and afterwards.

While I am grateful for the experience of serving as chair, I am very much looking forward to stepping back into to my old faculty role in which I get to teach more (hands down my favorite part of my work) and engage more heavily with my research. Next year I will return to teaching the first half of the U.S. history survey and upper level and graduate courses on the history of the United States during the Antebellum, Civil War, and Reconstruction Eras. I also will be able to dedicate more time to writing a monograph that has been long in the making – a biography of 19thcentury African American activist, Jermain Loguen, who was one of the primary Underground Railroad operatives in New York State.

I am excited to pass the torch to Jeff Helgeson, who is a natural leader in the department already and whose dynamism and commitment will surely take the department to new heights!

A Note from Dr. Jeffrey Helgeson

It is an incredible honor to be able to say that in September 2020 I will be beginning my eleventh year here at Texas State in a new role as chair of the department of history. Over the course of the past decade, I have had the great good fortune to learn from, and have the support of, our previous chairs: Dr. Frank de la Teja, Dr. Mary Brennan (now Dean of the College of Liberal Arts), and Dr. Angela Murphy. To a great extent, as leaders of the history department, they have created the foundation for my success here as a scholar and a teacher, and they have helped guide the energy I have put into helping to foster the growth of Texas State as a whole (the kind of work academics label, “service,” that includes not just serving on committees, but, among other things, making decisions about how we will teach our classes, who we will hire, and how the university can live as a community of inclusiveness and student growth in difficult times). I hope to follow in the footsteps of the previous chairs, to support my colleagues in their work.

The history department has a reputation for being a well-run department. This means that the chairs who have come before me have been highly successful at doing the work of managing the department. They lead the way on the work that happens behind the scenes to make sure that students have the classes, advising, and academic support they need. They work to ensure that our faculty has the resources they need to develop their research, as well as coursework and extracurricular programs (study abroad, study in America, student clubs, teacher training programs, etc.) that make the Texas State history department such a vibrant place.

The Department of History is a dynamic living community, the health of which depends upon the dedicated work of dozens of people. Our academic counseling and teacher training leaders are amongst the leaders in Texas and the nation. Our public history program has established itself as a national leader, placing graduates in internships and jobs with institutions like the National Park Service, the Smithsonian, and dozens of museums, archives, and history enterprises nationwide. Our undergraduate major in history prepares students to be leaders in the professional worlds of education, the media, public service, the arts, and much more. Moreover, through our connections with vibrant areas of study across campus—including, but not limited to, the Center for International Studies, the Center for Texas Music History, the Center for the Study of the Southwest, the Center for the Study of Gender and Diversity, and minors in African American and Latino/a Studies—the history department opens doors for students to have a grounding in sophisticated historical thinking while pursuing academic and career paths that could take them literally anywhere in the world. None of this wide-ranging work would be possible if not for the department’s outstanding administrative staff—I know I am going to learn so much from Madelyn Patlan, Roberta Ruiz, Adam Clark, and the student staffers in the office.

As you can see, I am a big believer in the ongoing work of the Department of History. I have seen my colleagues dramatically transform the lives of thousands of students over the years. I want to do nothing that will slow down those achievements. Indeed, one of my goals is to sustain the department’s record of continuous excellence, and to build upon recent gains we have made in funding graduate student research and travel, in creating resources to foster undergraduate research, and to support our faculty in their awe-inspiring research on historical themes that span thousands of years of global history.

In addition to maintaining our ongoing success, I also pledge my energies to the tasks of making the Department of History a place where even more students—undergraduate and graduate, alike—can find a path for themselves, while gaining the kinds of skills and worldview that will give them the power to constantly reinvent themselves in the face of life’s inevitable challenges. This means that I am committed both to the fostering of a community of scholars, even as I show up day in and day out to ensure that the nitty gritty work of making the department run well gets done.

Looking forward, I have to admit that I find my new role to be somewhat daunting. Yet I return to advice I received years ago from none other than my own mom. She said, if you want to take on big challenges in life, be sure to surround yourself with people whom you respect and who are doing interesting things. The Department of History is a complex institution, it is also my academic home—a place where I look forward to learning from, and working alongside, fellow faculty members, deeply competent and friendly staff, as well as curious and profoundly interesting students.