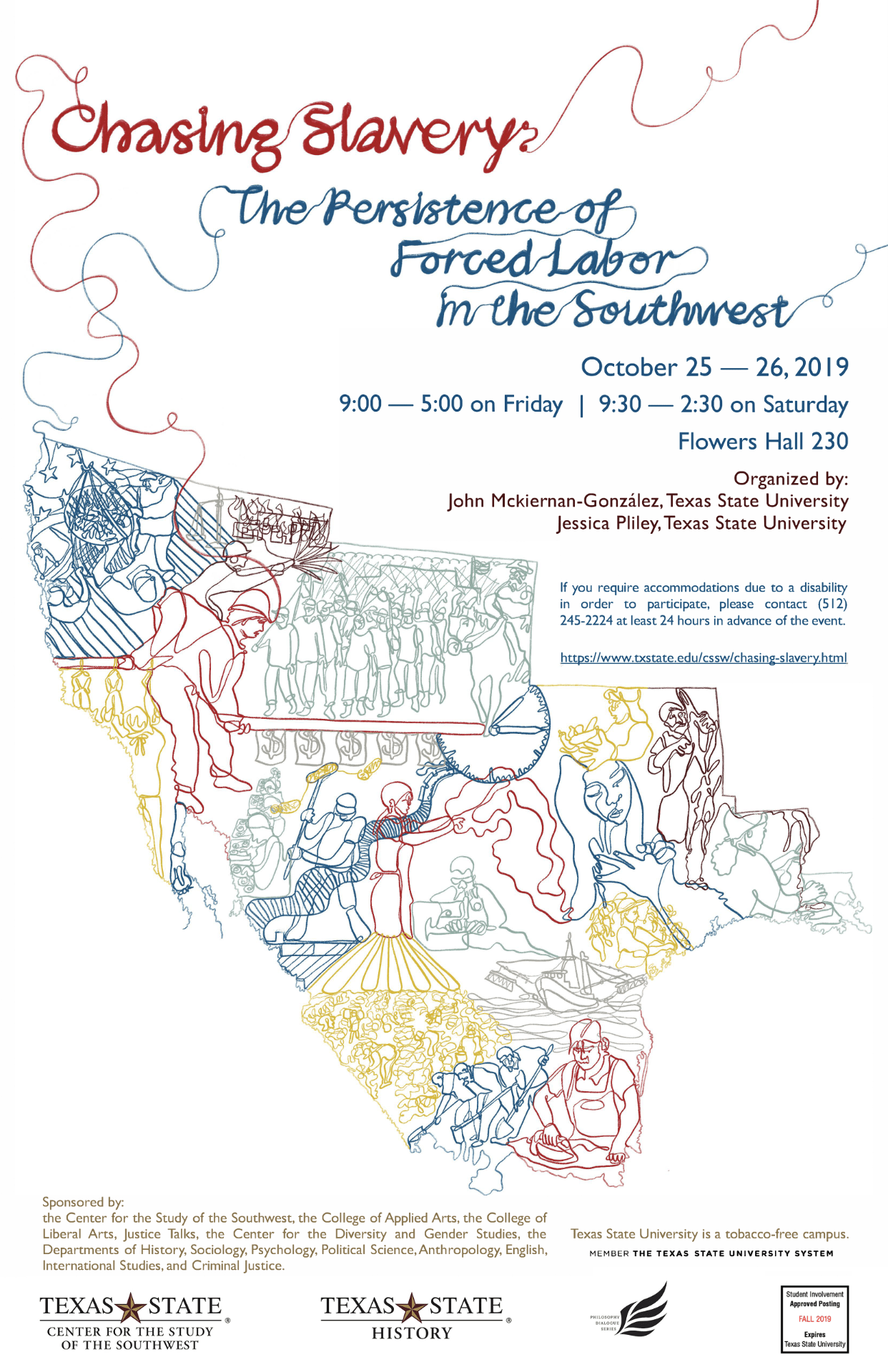

In preparation for the upcoming symposium, Chasing Slavery: The Persistence of Forced Labor in the Southwest, to be held at Texas State University from 24-26 October, in Flowers Hall 230, we will be running a series of posts focused on the conference participants and organizers. The conference will bring together dozens of scholars, with a keynote from Ambassador Luis C.deBaca (ret.). See the conference website for more details.

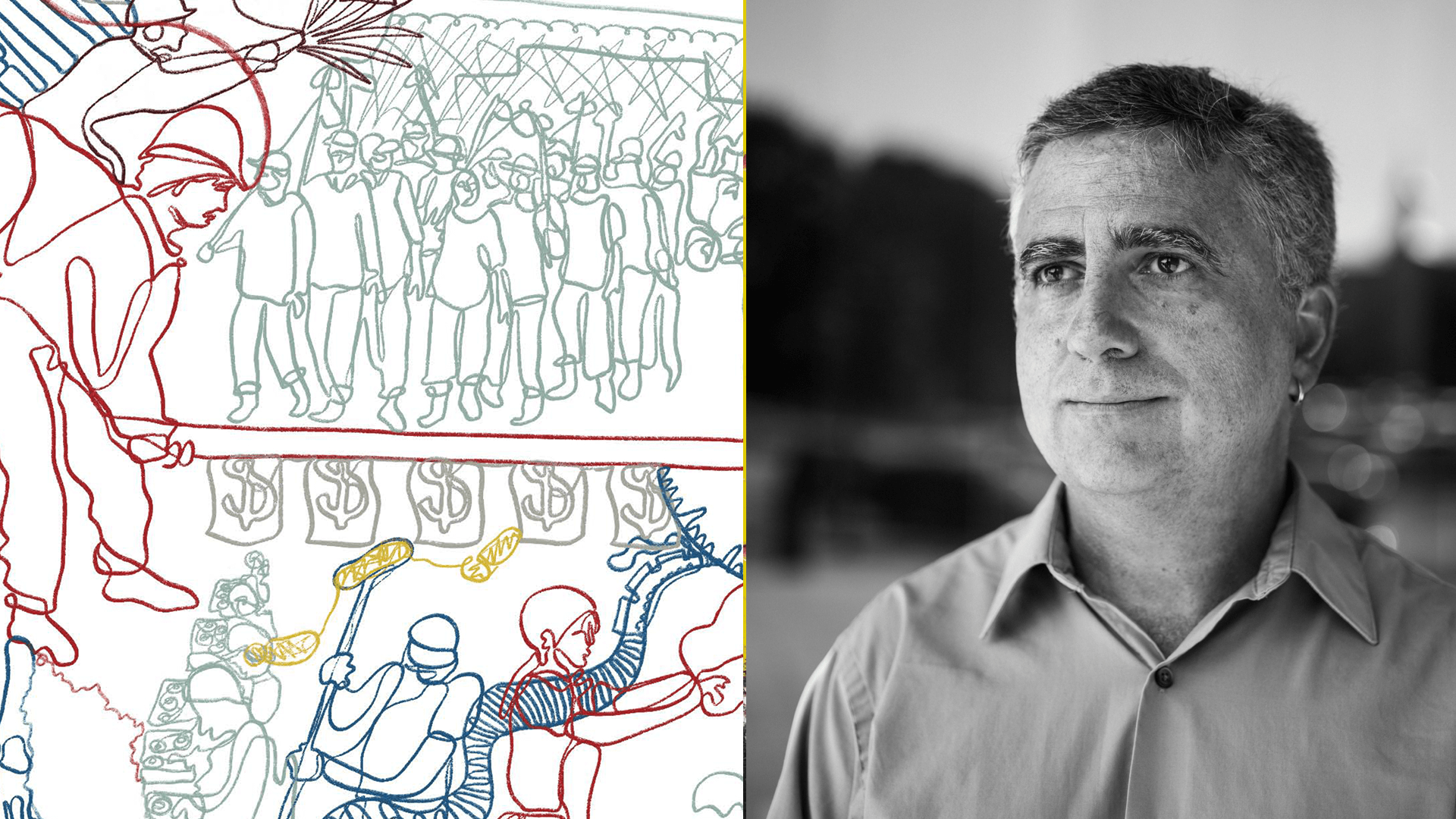

Today, conference participant Dr. Robert T. Chase, Associate Professor of History at Stony Brook University, shares with us a bit about his forthcoming book.

Tell me in four sentences why I should read your book.

Tell me in four sentences why I should read your book.

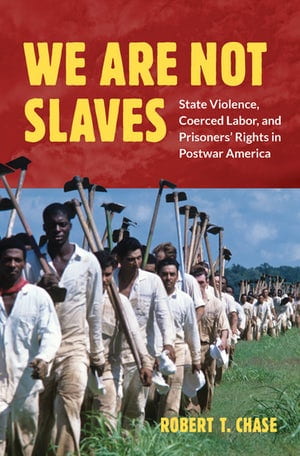

Dr. Robert T. Chase: We Are Not Slaves will be the first study of the southern prisoners’ rights movement of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s and the subsequent construction of what many historians now call the era of mass incarceration. By placing the prisoners’ rights movement squarely in the labor organizing and civil rights mobilizing traditions, my work reconceptualizes what constitutes “civil rights” and to whom it applies. My book shows that this prison-made civil rights rebellion, while mounting a successful legal challenge, was countered by a new prison regime – one that utilized paramilitary practices, gang intelligence units, promoted privatized prisons, endorsed massive prison building programs, and embraced 23-hour cell isolation—that established what I call a “Sunbelt” militarized carceral state approach that became exemplary of national prison trends. In this two-part narrative of resistance and punitive reconstitution, prison labor is treated as more than work; rather, prison labor constituted a regime of carceral discipline and power that ordered prison society, sexuality, white privilege and racial hierarchy. By drawing on newly released legal documents and over 80 oral histories with prisoners, this book considers the intersectional nature of prison labor as a cite of power that intersected with spatial control, gender identity, sexuality and sexual violence, and race and racial privileges. Rather than consider prison rape as an endemic feature of individual prisoner pathology, my study uses legal testimonies to excavate a changing prison society centered on labor division that controlled an internal sex slave trade that amounted to what what I call “state-orchestrated prison rape.”

What was the most surprising thing you encountered when researching your book?

Dr. Chase: The most surprising thing I encountered is the degree to which our criminal justice system relies on prevarication and outright lying to craft false narratives that incarceration offers modernization and rehabilitation, when, in point of fact, incarceration is, at its base, a system of state violence and coerced labor that ultimately eliminates people as citizens and as human beings. As a civil rights scholar, I expected to find in these civil rights cases the all-too frequent allegation of corporal punishment and physical abuse. But I never expected to find a system where fellow prisoners operated as guards over other prisoners where these “convict-guards” engaged in torture, maiming, daily abuse, and the sexual assault of other prisoners in a system that was sanctified by state power. By drawing on legal testimonies and by conducting oral histories with the incarcerated, I learned that prison rape was a system of state-orchestrated sexual assault as a state reward for those prisoners who acted as guards. As I shifted through personal papers, diaries, letters, and affidavits from the incarcerated, I became astounded at how these people who had so little formal education, learned to educate themselves, to become what are known as “jail house attorneys,” and how deeply these self-taught prisoners read philosophical and political treatises, and how such individual acts of “mind change” lent themselves to inter-racial political organizing in a racially segregated prison system that constituted a twentieth century “prison plantation” system that rendered these prisoners as literal “slaves of the state.”

What do you hope people will take away from our conference on trafficking, forced labor and labor exploitation?

Dr. Chase: I really appreciate the thematic approach of this conference that has taken normally separate fields of study – sexual trafficking, mass incarceration, and coerced labor – to instead put these fields in dialogue with one another to show how taken together these topics all too often operate as overlapping systems of oppression and dehumanization. Too often we think of “labor” as merely “work,” rather than the more comprehensive role that labor plays as a critically constitutive system that tends to divide society along strictly policed lines of race, ethnicity, class, gender, and sexuality. When we think about labor as more than work and as a constitutive process of division, we can better reimagine our collective “work” as crossing these socially constructed divides to build bridges and collective communities to combat such societal divisions.

What challenge(s) raised by your research are you still trying to reconcile?

Dr. Chase: When I started this research in the early 2000s, there were relatively few historical studies of twentieth-century prisons and almost none of the prisoners’ rights movement. Despite the development of a “long civil rights movement” historiography, I found that the literature simply did not discuss the ways in which what we now call mass incarceration has turned the gains of the civil rights revolution into another age of racial disparity.

My contribution to this rethinking of post-1965 narratives is to demonstrate that the civil rights rebellion reached prisoners as well and that their collective efforts extend the struggle for civil rights into the decades of the 1970s and 1980s. Moreover, my use of oral histories, legal depositions and affidavits, and courtroom testimony provides an example to students of the ways in which they can uncover the voice and agency of the prisoners themselves. Despite winning the nation’s largest civil rights victory against unconstitutional prison systems, however, the Texas prisoners’ rights movement found that the ground had shifted underneath their feet and that just as the southern prison plantation fell, the new “Sunbelt” militarized prison arose from its ashes like a carceral phoenix.

When activists, abolitionists, policy makers, and reformers attempt to curb mass incarceration, they must seek redress not only at the federal level through national legislation but perhaps more importantly they must encounter the ways in which policing and mass incarceration are governed at the local and state level where the American state is indeed strong. One suggestion that my book offers is that social justice movements against mass incarceration should continue to focus as much attention on changes in local and state government as the civil rights movement once did when it sought civil rights as a matter of national and federal intervention. To dismantle this encompassing thicket of mass incarceration, we must utilize the spade of history to reveal just how deep we must cut to reach the roots of intertwining carceral states.

Also check out:

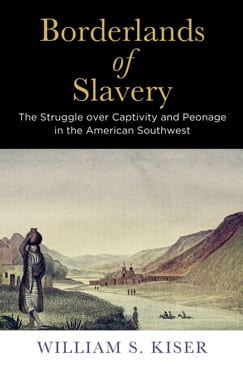

- We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America

By Robert T. Chase (University of North Carolina Press, 2020) - Caging Borders and Carceral States: Incarcerations, Immigration Detentions, and Resistance

Edited by Robert T. Chase (University of North Carolina Press, 2020)