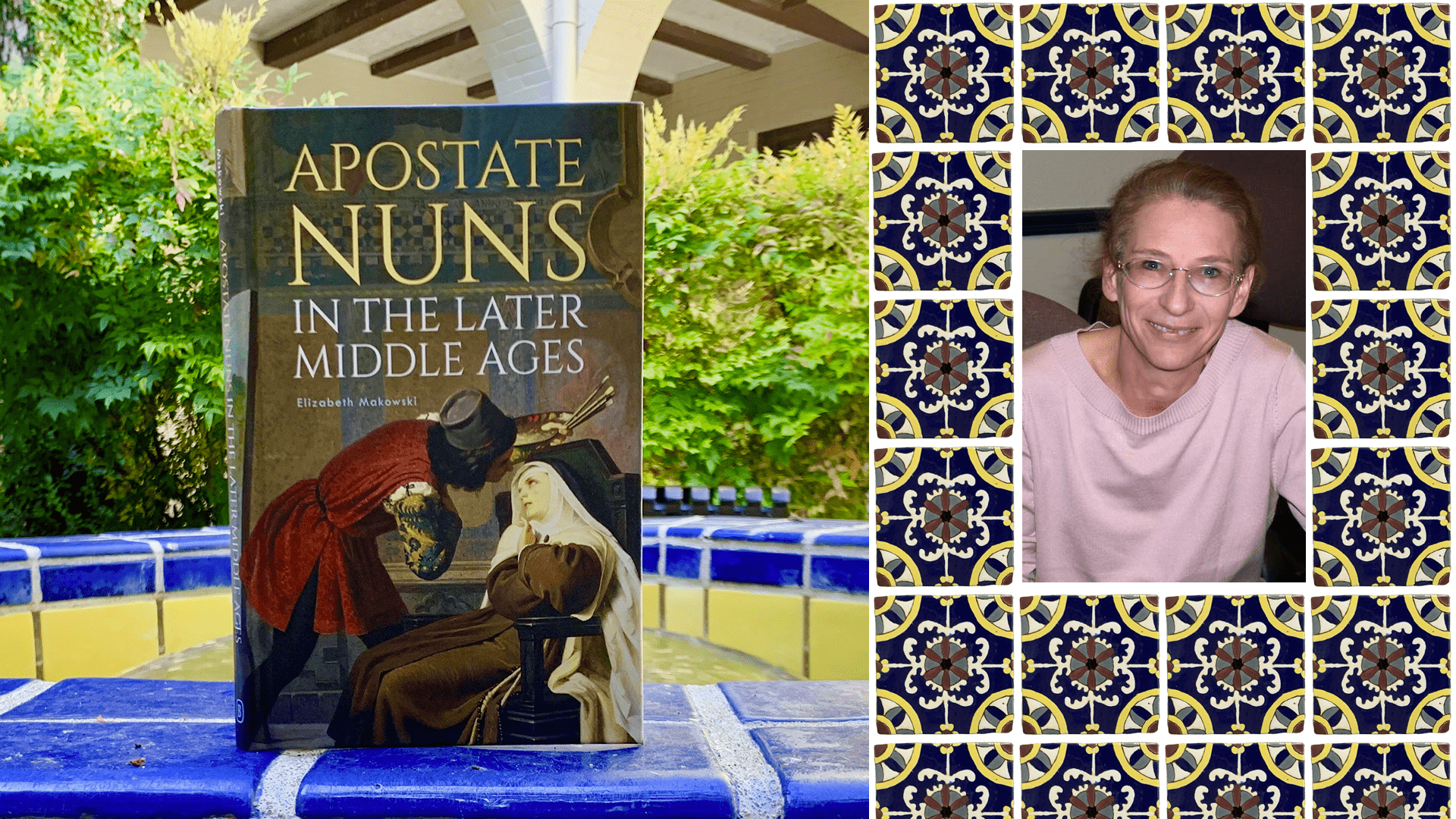

Emerita Professor of History Dr. Elizabeth Makowski recently released her new book, titled Apostate Nuns in the Later Middle Ages (Boydell and Brewer 2019, 30% discount using promo code: BB130).

Dr. Makowski took the time to answer a few questions about her new book and the research behind it!

Book description: “To make a vow is a matter of the will, to fulfill one is a matter of necessity,” declared late medieval canon law, and religious profession involved the most solemn of those vows. Professed nuns could never renege on their vows and if they did attempt to re-enter secular society, they became apostates. Automatically excommunicated, they could be forcibly returned to their monasteries where, should they remain unrepentant, penalties, including imprisonment ,might be imposed. And although the law imposed uniform censures on male and female apostates, the norms regarding the proper sphere of activity for women within the Church would prohibit disaffected nuns from availing themselves of options short of apostasy that were readily available to monks similarly unhappy with the choices that they had made.

This book is the first to address the practical and legal problems facing women religious, both in England and in Europe, who chose to reject the terms of their profession as nuns. The women featured in these pages acted, and were acted upon, by the law: the volume shows alleged apostates petitioning for redress and actual apostates seeking to extricate themselves, via self-help and litigation, from the moral and legal consequences of their behaviour.

Q: What question(s) did you hope to answer when you started this book?

Dr. Elizabeth Makowski: The unanswered questions with which I was left after finishing my book on cloister regulation of nuns (Canon Law and Cloistered Women) really led to all of my subsequent research projects. Exploring Pope Boniface VIII’s vaunted effort (the papal bull, Periculoso, 1298) to impose strict enclosure upon “all nuns of every order throughout Christendom,” made me curious about the ways religious women who were not technically nuns were treated by Church lawyers and pundits (A Pernicious Sort of Woman). Then I began to wonder how women who were nuns, and who actually tried to implement strict cloister rules, managed to stay financially solvent (English Nuns and the Law in the Middle Ages). I was drawn to the topic of apostate nuns since the rules for the recognition, return, and reintegration of apostate monks and nuns were established at just about the same time that Pope Boniface had attempted to, and at least partially succeeded in, making life for female regulars considerably different from that of their male counterparts. When I began to investigate, I found that scholars had not given very much attention to the topic of female apostasy and that convinced me to begin my own research.

Q: What major challenges did you face in doing this research?

Dr. Makowski: Work on this book was interrupted by a major family health crisis so it was a slow process. I reckon it was seven years in the making and because of the gap between beginning the research/writing, and submitting a draft to my editor at Boydell and Brewer, I had a very hard time crafting the manuscript into the best, most cohesive book it could be. Integrating the suggestions for revision, given by the readers to whom the manuscript was sent, while remaining true to my initial vision for this book was indeed a challenge. Thanks to those capable and thorough reviewers, and the patience of my editor, well, you can judge for yourselves.

Q: What type of primary sources/archives did you consult?

Dr. Makowski: The most important primary sources used for this book fall into roughly three categories. First, canonical rules and regulations governing apostasy; legislative and doctrinal material that became the formal, normative law. Second, case material and other documents of practice that tell us something about the implementation of that law. Third, contemporary narratives about apostates that provide some insight into the lived experience of both apostate nuns and those charged with their return and reintegration to monastic life. While some of these original sources have been published—the defining books of the Corpus Iuris (the collection of medieval Church law) for instance— a great deal of other important prescriptive literature, such as consilia, (legal opinions written by academic canonists for use by court or client), and many episcopal registers, episcopal commissary and audience court records, Chancery wits, and proceedings in royal or papal courts have not. All sources, even published chronicles such as Iohannes Busch, Chronicon Windeshemense Und Liber De Reformatione Monasteriorum, are generally untranslated, and with the exception of excerpts from them that appeared in, and are quoted from, secondary scholarship, all translations and paraphrases are mine.

Q: What was something surprising that you found in your research?

Dr. Makowski: Oh, there were so many surprises! For example, many nuns who left their convents later actually sought to return to the vowed life, although the circumstances of an apostate’s secular existence were real considerations in decision-making; motherhood in particular often tipped the balance. Lucrezia Butti had attempted to recommit herself to religious life after the birth of her son, but left again, for good, soon after. Battistina, professed nun who had fled her convent of Poor Clares to live for years with, and have children by, a Milanese layman, begged the Sacred Penitentiary for absolution and the opportunity to return to religion only after her children were grown; and it was not until after the death of her son that Sophie of Brunswick reconsidered her resolve to remain in the world.

I was also struck by the variety of reasons for, and means by which, these disaffected nuns became apostates. The prospect of inheriting great wealth by renouncing one’s religious status was a compelling lure for some, but romantic love, lust, or a combination of both, motivated far more professed nuns to become apostates. Some apostates were reluctant renegades set adrift by war and disaster, lapses in judgment, or religious reforms that consigned them to a life much more rigorous than they had ever promised to live. Some broke with the vowed life suddenly, others strayed from it by degrees.

And then there were the legal ambiguities that could trip up an unwary researcher! Relatively lax regulations regarding the admission of male clergy and laymen into cloister confines could result in what was technically referred to as raptus, ravishment, an ambiguous term which was used by scribes and lawmakers to mean both rape (sexual assault) and abduction, forced or consensual. In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, it became part of the formula to initiate a case in civil and criminal courts, but it might just as easily have denoted a nun’s voluntary abandonment of her vows as sexual violence and forceful seizure. Even if an escape plan was hatched by someone other than the apostate herself, collusion can seldom be entirely excluded from the equation.