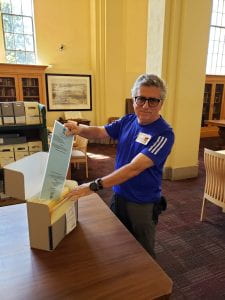

In June 2023, I spent most of three weeks in two Stanford University Special Collection libraries, the Lane Medical History Center and the Special Collections and University Archives in the Green Library in Stanford. My general interest is Latinos, health care and social justice, so I decided to spend some extended time in the Ernesto Galarza papers. What I found in the folders and papers linked to the National Farm Laborers Union troubled my regionally-bound assumptions regarding the source and inspiration of labor organizing. The first hint that I might be remiss in my assumption that Latino farm labor organizing happened alongside the Pacific migration circuits connecting the western states of Nayarit, Jalisco and Michoacan to the U.S. Pacific Rim encompassing California, Oregon and Washington. You can see the importance of the U.S. and Mexico in the many of the photographs. Ernesto Galarza himself makes this very clear in his autobiography, Barrio Boy, where he narrates his upbringing in rural Nayarit and his migration to the U.S. in the 1920s.[1]

I was a little remiss in my assumption regarding what side of the Pacific, and which migration. NFLU organizer Hank Hasiwar told Donald Grubbs that he got involved in farm labor after his “armed service in Japan. There he had gained first hand knowledge of the land redistribution and peasant ownership program instituted by known reformer General Douglas Macarthur, whose Japanese Radicalism the NFLU hoped to transplant into the soil of California’s San Joaquin Valley.”[2] This is not the first time democracy movements at the edge of the U.S. empire helped shape reform movements in the United States, but the impact of seeing land transfer from landowners to peasants and migrant workers under U.S. occupation demonstrated that land reform “si se puede,” at least to that New Deal informed GI. As much as the Great Depression drove Black, White and Mexican Southern families to California, World War II enabled the migration of young American men to Japan, where they learned that societies could be reshaped, giving voice to peasant families in what been an imperial monarchy.

WWII may have brought Galarza and Hasiwar together. The Ernesto Galarza Papers Collection also made it clear that the NFLU – both Galarza and Hasiwar – were in close contact with their parent organization, the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union. Galarza regularly reported to HL Mitchell; Congress regularly called HL Mitchell to task for the labor actions NFLU affiliates started taking in post-WWII rural California, most notably the secondary boycotts against the Di Giorgio Farm Corporation. It is here, in the folder titled “Spiders in the House,” TV Program KNBC Los Angeles Mounted Photos,” that materials from a 1940s publicity campaign by the Southern Tenant Farmer’s Union appeared. The jutting chin, the short-sleeves, the blurry clouds in the background, the angle from below and the undeniably charismatic model for the photograph titled “New Farmworker in the South” pointed to both the national aspiration and cross-regional impact of rural organizing in the Appalachians and the Tennessee River Valley.[3] Historian Jeffrey Helgeson pointed out how this 1940s photo’s staging evoked painter, African American activist and labor exile Charles White’s depiction of Black Southern life.[4] This even carried through to the Di Giorgio strike where – even though the NFLU stood for Mexican American and Asian American Civil rights, 90% of the 800 striking workers were white and with southern roots, making it hard for the NFLU claiming to strike a blow for civil rights in California. The “new Southern farmworker” may have represented the hope for the STFU and the NFLU. Their success at negotiating as farmworkers contributed to the ensuing backlash from the California chapter of “Rancher Nation,” the Associated Farmers of California and their lawyer, Richard Milhouse Nixon.[5]

Maybe many of these workers had also been part of the occupation of Japan and maybe they too knew of the possibility of radical transformation alongside federal involvement. The NFLU and the STFU organized rural workers and rural communities, and they drew on as many organizing traditions to be successful, be they imperial and revolutionary, Mexican or Appalachian, rural and industrial. The success of the secondary boycott against Di Giorgio Produce in California contributed to a senate hearing on secondary boycotts’ which probably influenced those anti-boycott provisions in the Taft-Hartley Act. Farm workers and labor organizers like Hazimwar suffered the brunt of shifting national objectives, from imposing land transfers in Japan to imposing labor controls in the rural United States.

All this is to say – using photographs of meetings in Tijuana, Salinas and Memphis – is that an archive helps reveal the particular ways the world can be deeply entangled, and that labor organizing in central California drew from traditions in the United States, Mexico, the Philippines, Japan and even radical conservatives in the U.S. Arny central command.[6] It helps to read widely to recognize the cross-regional entanglements; it helps to have extended time to chew on the miscellanea in various folders across the archive, to read against your assumptions shaping your reading of the collection. I mean, I came to the Galarza archive to see whether specific medical issues facing farmworkers had been part of the organizing brief for NFLU labor organizers. Instead, I learned of the broad cross-regional milieus shaping federal agricultural policy in the Western United States.

[1] Ed Frayne Photography, Salinas, California. “Farm Labor Union Meeting,” Collection 224, Ernesto Galarza papers, Box 65, Series V, Folder 8, Folder Title, Farm Labor Union Meeting, Salinas, California, circa 1948.

[2] Donald Grubbs, “The National Farm Labor Union in California: background to Cesar Chavez,” typescript, Folder 2Title Braceros, Living and Working Conditions, 1949-1957, Series V, Box 65, Collection 224 Ernesto Galarza papers. John Dower, noted historian of the relationship between Japan and the United States, emphasized the democratizing impact U.S. constitutional reforms had on working-class and rural Japan; I am confident few people have examined the democratizing impact these Japan-specific reforms may have had on U.S. soldiers. John Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II (NY: W.W. Norton, 1999)

[3] Southern Tenant Farmworkers Union, ”New Farm Worker of the South, n.d.” Box 65 Folder 10 “Southern Tenant Farmers Union, living and working conditions in the South, ca. 1940s,”

[4] Vanessa Cross, “African American Artist Charles W. White Jr.” American Artist Blogspot, http://american-biography.blogspot.com/2011/02/african-american-artist-charles-w-white.html Adapted from Vanessa Cross, “Charles White: the Art of a Chicago Son Beautifies Experiences of Common Black Folk,” Afrique June 1996.

[5] Ernesto Galarza, Spiders in the House and Workers on the Field (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1970)

[6] Lori Flores, Grounds for Dreaming: Mexican Americans, Mexican immigrants and the California Farmworkers Movement (New haven: Yale University Press, 2018); Christian Paiz,The Strikers of Coachella: A rank-and-file history of the UFW movement (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2022). See also the first draft of this history in Ernesto Galarza, Spiders in the House and Workers in the Field (Notre dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1970)